First published in the July, 2025 Homesteader newsletter

Amid the depths of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt formulated a bold plan for putting millions of unemployed Americans to work on the nation’s public lands. Between 1933 and 1942, over 86,000 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) enrollees worked on Oregon’s national forests, state parks, and tribal lands. Their labor transformed the landscape and created some of the state’s most beloved recreational areas.

The scale and scope of their accomplishments are staggering. In Oregon alone, the CCC built 50,000 miles of forest roads, 20,000 miles of trails, 3,000 acres of public campgrounds, 1,500 bridges, and hundreds of fire lookouts. CCC crews risked their lives fighting epic wildfires and restoring Oregon’s damaged forests. Today, it’s almost impossible to travel around the state without encountering reminders of their legacy, from irrigation canals to ski lodges.

During those years, the CCC was active in Central Oregon with several camps assigned to the Deschutes National Forest. The Forest Service hosted main camps at Crane Prairie, Camp Sherman, Odell Lake, Cabin Lake, and several temporary side camps. Camp Sisters was the longest-running camp in Central Oregon. It opened in 1934 and was one of the largest CCC camps in the United States. The Forest Service originally planned to build the camp outside Sisters; however, they eventually placed it near the headwaters of the Metolius River around the present site of the Riverside Campground. Despite its location, the camp kept its original name.

Camp Sisters enrollees developed many recreational amenities in the area, including the 11-mile road along the lower Metolius River. They constructed picnic and campground facilities along the upper Metolius and walking trails along both sides of the river. Crews built shelters at Camp Sherman, Pine Rest, and Pioneer Ford, as well as a fire lookout on Trout Creek Butte, west of Sisters.

From 1935 to 1937, Camp Sisters enrollees worked on recreation facilities along the south shore of Suttle Lake around what is now the Cinder Beach Day Use area, adjacent to the Suttle Lake Resort. Projects included a campground, trails, picnic areas, and outdoor fireplaces. The toilet building and picnic shelter at Cinder Beach are original CCC designs. In 1936, enrollees constructed the Suttle Lake-Camp Sherman Road and improved the Scout Lake Road. In 1938, another crew assigned to the Deschutes National Forest cut a five-mile cross-country ski trail skirting Blue Lake and Suttle Lake. They also helped improve recreational amenities around Dark Lake and Camp Tamarack, which had just opened a few years earlier.

Around the same time, workers employed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were building Bend’s famous Skyliners Lodge, but CCC crews helped develop much of the adjacent infrastructure. Enrollees helped clear and grade the ski slopes, built a cross-country skiing loop trail, and constructed warming shelters around the lodge while working from a temporary side camp along Tumalo Creek.

The CCC completed several projects within what became the Newberry National Volcanic Monument. The

projects included cutting the road into Newberry Crater in 1933 and building the Paulina Lake Guard Station in 1938, now housing the Paulina Visitors Center. The CCC also built and refurbished several fire lookouts in the Deschutes National Forest, including structures at Trout Creek Butte, Black Butte, and Fox Butte.

Cabin Lake was another CCC camp within the national forest. It was located near Fort Rock and was active from 1934 to 1938. Enrollees from Cabin Lake built an administrative complex adjacent to the camp, which became the headquarters of the Fort Rock Ranger District. They constructed several buildings, including a ranger residence, two additional cabins, a warehouse, a maintenance shop, and a gas house. A few of those structures are still in use today.

The CCC crews assigned to the Sisters and Odell Lake camps did much of the early development work at the Pringle Falls Experimental Forest, established in 1931. One of the CCC’s first tasks involved thinning and mapping the original research plots. Other projects included building residences and offices and assisting with research projects. CCC crews were trained to use surveying instruments to map the experimental forest and also helped with data collection and sampling to support the site’s research.

The CCC’s Work for the Bureau of Reclamation

The CCC had around a dozen camps in Oregon assigned under the Bureau of Reclamation. Those projects involved rehabilitating water storage and distribution systems, flood control work, and the construction of canals, dams, and reservoirs. The CCC provided labor for some of Oregon’s most ambitious reclamation efforts, including the Deschutes Project in Central Oregon.

When Congress approved the Deschutes Project in 1937, it tasked the bureau with managing the work. The project involved developing a large water storage reservoir in the Upper Deschutes Basin, east of La Pine, and a 65-mile canal delivering water from a diversion off the Deschutes River south of Bend, supplying water to the Madras area in Jefferson County.

During the 1930s, the bureau used CCC enrollees mainly as unskilled labor for canal excavation, clearing brush, placing riprap, building roads, and stringing telephone lines. However, under time pressure, the bureau needed to make better progress. Eventually, it employed the CCC crews to do as much work as possible on the Wickiup Reservoir and North Unit Canal. This included operating heavy machinery and helping with blasting work. However, the bureau still contracted with private companies for the project’s more technical aspects, such as constructing the dam works at Wickiup.

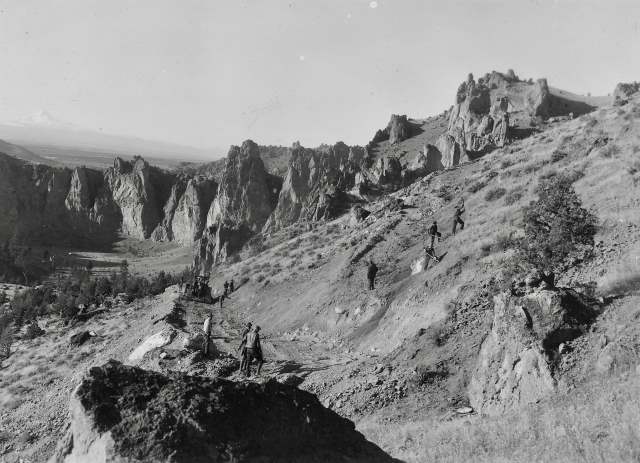

The first CCC company arrived in Redmond in June 1938, reassigned from another reclamation site at Stanfield in Umatilla County. They began building their camp east of Redmond, which The Bulletin described as “not merely a camp, but rather a CCC city” since it was three times larger than the typical CCC camp. Once they established the camp, enrollees began working on the sixty-five-mile central canal stretching from Bend through Smith Rock to Madras. At the same time, another group of enrollees worked from a seasonal camp at Wickiup near the proposed site for the dam and reservoir.

The first task for the Camp Wikiup enrollees was to build eight miles of road and telephone line from Pringle Falls to the dam site. Once that task was complete, enrollees began building the camp structures in the fall of 1938. They lived in tents for ten months while they finished the permanent barracks. When completed, the Redmond and Wickiup camps were the largest CCC work sites in the western United States, accommodating three companies of 200 men each.

Camp Wickiup was more elaborate than the typical CCC camp. It could house over 400 enrollees and had over thirty permanent buildings, including a testing laboratory and auditorium. Officials claimed it had the best-equipped infirmary of any CCC camp in the county, with a 15-bed ward. Once the enrollees finished the camp, they began the enormous task of clearing the reservoir site and erecting embankments. That job kept them busy for the next three years. By the fall of 1939, crews cleared over 700 acres of forest from the reservoir site.

The working season at Camp Wickiup ran from April to December. When the camp closed for the winter, the enrollees returned to Redmond and worked on the main canal project. This involved the exhausting task of clearing trees and rocks from the canal’s path and lining the excavated route with rock. Redmond-based enrollees built most of the canals and supporting infrastructure south of the Crooked River crossing. This included dozens of small bridges, flumes, and siphons. The CCC also helped excavate the open canal running through Smith Rock and creating the service route over Grey Butte, now known as Burma Road, overlooking the state park.

After the war began in December 1941, the CCC significantly reduced its commitment to the unfinished Deschutes Project. When the program ended in the summer of 1942, the CCC closed Camp Wickiup while the military took over the facilities at Camp Redmond. Unfortunately, the dam and reservoir were only about 20 percent complete when the CCC program ended. However, in December 1942, work resumed at Camp Wickiup under the Civilian Public Service program. The Mennonite Central Committee ran the camp, which opened with around 80 conscientious objectors. The following year, the Selective Service took over the site and ran the Civilian Public Service camp until it closed in July 1946.

The canal project was eventually completed in 1946, while the dam and reservoir became operational in 1949. When the North Unit Canal system was completed, it was one of the most important reclamation projects ever undertaken in Oregon, providing water for 50,000 acres of farmland. The project transformed the area from dry crop agriculture into one of the most productive farming areas in Central Oregon. The Deschutes Project would likely never have been approved or completed without the contribution of the CCC and the Civilian Public Service draftees.

Conclusion

By the time the CCC ended in 1942, Oregon had benefitted far more than most states from the New Deal-era recovery programs. Because of the state’s large percentage of federally managed lands, Oregon received disproportionate labor and funding from programs like the CCC. Only a few states hosted more camps during the program’s nine-year run. Oregon ranked 12th in the nation in per capita federal expenditures from the CCC and other New Deal programs. Between 1933 and 1942, the CCC accomplished an astonishing amount of work in Oregon, building hundreds of bridges and fire lookouts, planting over 40 million trees, and spending nearly a million hours on firefighting and post-fire forest restoration. They developed many of the state’s most beloved recreational sites and scenic areas. Those achievements were unprecedented in American history and created a legacy enriching the lives of Oregonians to this day.

Glenn Voelz is a local author and serves on the Deschutes County Historical Society board. His most recent book, The Civilian Conservation Corps in Oregon – A Living Legacy, is available at the Deschutes Historical Museum. Click here to purchase a copy online.